The British Empire and Its Colonies: How Britain Shaped—and Was Shaped by—the World

Explore the vast history of the British Empire and its colonies—from its rise and global expansion to its legacy and lasting impact on culture, trade, politics, and identity across continents.

CULTUREHUMANITY

7/27/20259 min read

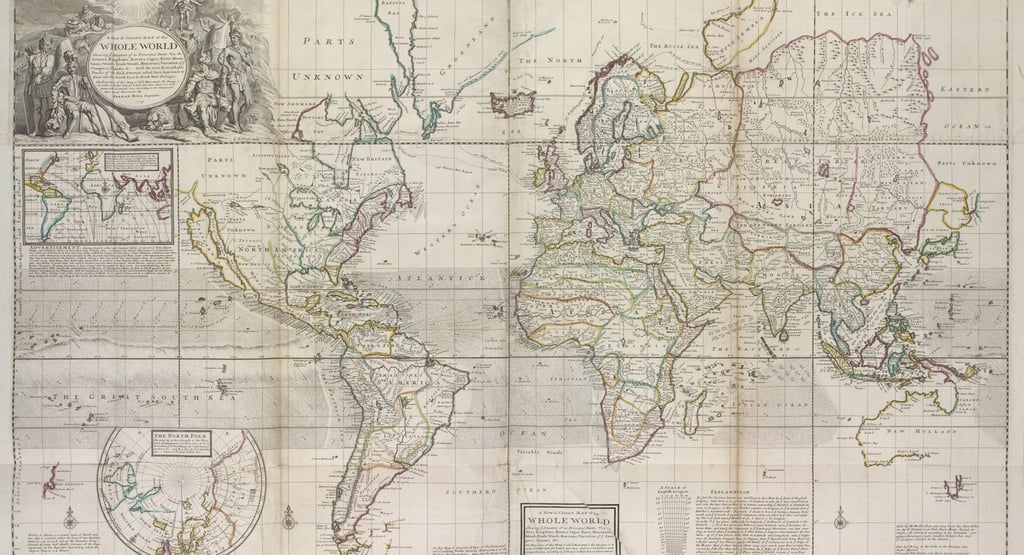

Few empires in human history have left as deep, complex, and far-reaching an imprint on the world as the British Empire. Spanning every continent, ruling over nearly a quarter of the world’s population at its peak, and encompassing colonies from the Caribbean to the Pacific, the British Empire profoundly influenced politics, economics, culture, and identity across centuries.

The story of the British Empire is not just one of conquest and power—it is also a tale of ideas, innovation, exploitation, and resilience. It represents both the zenith of imperial ambition and the moral reckoning that followed. From London’s merchant docks to the tea plantations of India, from the slave ships that crossed the Atlantic to the independence movements that reshaped the 20th century, the British Empire’s history is woven into the modern world.

This article explores the rise, expansion, governance, economic systems, culture, and decline of the British Empire, as well as its legacy in today’s global society.

1. The Origins of the British Empire

The British Empire did not emerge overnight. It began modestly, in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, when England—still recovering from internal strife and dynastic conflicts—looked outward for opportunity. The reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) marked the dawn of English exploration and naval ambition.

1.1 The Age of Exploration

Inspired by Spain and Portugal’s global ventures, English explorers such as Sir Francis Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh, and John Hawkins set sail to find new trade routes and territories. Their missions blended commerce, piracy, and colonization, often backed by royal charters granting monopolies and privileges.

The founding of the Virginia Colony (Jamestown, 1607) marked the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It signaled the beginning of Britain’s colonial era, driven by trade, wealth, and the growing belief in mercantilism—the idea that national power depended on the accumulation of gold and control of trade.

1.2 The Role of Chartered Companies

In the early empire, private enterprises played a key role. The East India Company (1600) and the Hudson’s Bay Company (1670) were granted monopolies to trade in Asia and North America. These companies effectively acted as mini-governments, maintaining armies, negotiating treaties, and administering territories—all for profit.

This era saw Britain begin to weave a global web of influence through commerce rather than conquest, laying the foundations for what would become the largest empire in history.

2. The Expansion of the British Empire

By the 18th century, Britain was emerging as a dominant global power. Its growing naval strength, combined with industrial advances and political stability, allowed it to compete with—and eventually surpass—its European rivals, especially Spain, Portugal, and France.

2.1 The Atlantic Empire: The Caribbean and the Americas

The 17th and 18th centuries marked Britain’s deep involvement in the Atlantic world, particularly through the transatlantic slave trade and plantation economies. Colonies in the Caribbean—including Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad—became central to Britain’s wealth, producing sugar, rum, and tobacco through the labor of enslaved Africans.

In North America, Britain established thirteen colonies along the eastern seaboard. These colonies thrived economically, though they also developed a distinct identity—one that eventually led to the American Revolution (1775–1783) and the loss of Britain’s most prosperous colonial possessions.

Despite this setback, the British Empire adapted, shifting its focus toward Asia, Africa, and the Pacific.

2.2 The Raj and the Jewel in the Crown: British India

Perhaps the most famous of all British colonies, India became the centerpiece of the Empire. The East India Company first gained trading rights in Mughal India in the early 1600s, but following the Battle of Plassey (1757), it began direct political control.

By the 19th century, Britain ruled India directly, calling it the “Jewel in the Crown” of the empire. India provided raw materials such as cotton, tea, and spices, and served as a vast market for British goods.

However, this relationship was not one of mutual benefit. British rule disrupted local economies, caused famines, and suppressed local industries. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 led to the dissolution of the East India Company, after which the British Crown assumed direct control, forming the British Raj (1858–1947).

2.3 Africa and the Scramble for Colonies

The Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century marked another stage of imperial expansion. Motivated by economic interests, nationalism, and the belief in the “civilizing mission,” Britain colonized vast territories across Africa—including Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia).

The Berlin Conference (1884–1885) saw European powers divide Africa into territories with little regard for indigenous boundaries. British colonies often developed dual economies—modern export industries alongside subsistence agriculture—creating structural inequalities that still persist.

2.4 The Pacific and Oceania

In the Pacific, British influence extended through colonization of Australia (1788) and New Zealand (1840), where indigenous populations were displaced or assimilated through force and cultural dominance. These colonies evolved into settler societies, later forming self-governing dominions within the empire.

Meanwhile, islands such as Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands also came under British control, forming an imperial network that spanned from Canada to the South Pacific.

3. Governance of the British Empire

Administering such a vast empire required adaptability and innovation. The British developed multiple systems of governance, tailored to different colonies’ strategic and economic importance.

3.1 Types of Colonies

Crown Colonies: Directly ruled by the British government (e.g., Jamaica, Hong Kong).

Chartered Company Colonies: Administered by trading companies under royal charter (e.g., British East India Company, British South Africa Company).

Protectorates: Territories under British protection but retaining local rulers (e.g., Egypt, Nigeria).

Dominions: Largely self-governing colonies with British allegiance (e.g., Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

Mandates and Trust Territories: Former German and Ottoman lands administered by Britain after World War I (e.g., Palestine, Iraq).

3.2 The Role of the British Monarchy and Parliament

While the monarch symbolized imperial unity, the real power lay with Parliament and the Colonial Office, which set laws and policies governing trade, defense, and diplomacy. Governors and viceroys implemented British interests locally, often with substantial autonomy.

3.3 The Colonial Bureaucracy and Education

The British often relied on a civil service elite—educated at institutions like Oxford and Cambridge—to administer colonies. Local elites were co-opted into governance structures through education and patronage. This created a colonial middle class in places like India, Malaya, and Africa, which later spearheaded independence movements.

4. The Economic Engine of Empire

At its core, the British Empire was an economic enterprise. Colonies were sources of raw materials, markets for manufactured goods, and opportunities for investment.

4.1 The Mercantile System

In the early period, British colonial policy was guided by mercantilism—a system aimed at maximizing exports and minimizing imports. Colonies existed to enrich the mother country through trade monopolies and resource extraction.

The Navigation Acts (1651–1660s) required colonial goods to be shipped only in English vessels, ensuring British control of commerce.

4.2 Industrialization and Imperial Trade

The Industrial Revolution (18th–19th century) transformed Britain into the “workshop of the world.” Imperial resources—cotton from India, sugar from the Caribbean, rubber from Malaya—fueled industrial production. In return, British textiles, machinery, and manufactured goods flooded colonial markets.

This relationship was highly unequal: colonies became economically dependent, while Britain grew wealthy. However, the empire also laid the foundations for global capitalism, connecting distant economies through trade networks, finance, and technology.

4.3 The Role of Slavery and Exploitation

The British Empire’s early wealth was built on the back of enslaved Africans, forcibly transported to the Americas. The triangular trade—manufactured goods from Britain, slaves from Africa, and sugar or cotton from the Caribbean—created enormous profits.

Although Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, its economic effects persisted for generations. Many former slave owners were compensated—while freed people received nothing.

5. The Cultural and Ideological Dimensions of Empire

The British Empire was not merely political or economic—it was also cultural. Imperial ideology shaped how Britons saw themselves and how they justified their rule over others.

5.1 The “Civilizing Mission”

Victorian Britain often viewed its empire as a moral enterprise—a duty to “civilize” the supposedly backward peoples of the world. This concept, rooted in social Darwinism and racial hierarchy, underpinned imperial education, missionary work, and cultural assimilation.

Missionaries spread Christianity, English education, and Western values, while suppressing indigenous beliefs and traditions. English became a global lingua franca—but often at the expense of native languages.

5.2 Cultural Exchange and Hybrid Identities

Despite its oppressive aspects, empire also facilitated cultural exchange. Cuisine, language, and art blended across continents. British culture absorbed Indian curry, Caribbean music, and African rhythms, just as colonized societies adopted English literature and sports like cricket and football.

These hybrid identities continue to shape multicultural societies across the Commonwealth today.

5.3 Empire and Science

Empire was both a laboratory and a vehicle for scientific discovery. British expeditions mapped unknown territories, studied flora and fauna, and classified the natural world. Yet this “knowledge gathering” often served imperial goals—helping to control resources and peoples more efficiently.

6. Resistance, Nationalism, and the Winds of Change

While the British Empire projected power and prestige, it was never uncontested. Resistance—both violent and nonviolent—was a constant feature.

6.1 Early Resistance Movements

From the Maroon communities of escaped slaves in Jamaica to uprisings in India, Ireland, and Africa, resistance took many forms. Some revolts were crushed brutally, while others laid the groundwork for political consciousness.

6.2 The Rise of Nationalism

The 20th century saw the emergence of organized nationalist movements across the empire. The two world wars, economic crises, and growing global awareness accelerated demands for independence.

In India, figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru mobilized millions through nonviolent resistance. In Africa, leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) and Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya) led liberation struggles. In Southeast Asia, movements in Malaya, Burma, and Singapore challenged colonial authority.

6.3 The Decline and Fall of the British Empire

The empire’s decline began after World War I, when maintaining vast overseas territories became economically and politically unsustainable. The Suez Crisis (1956) symbolized Britain’s reduced global influence, as the United States and Soviet Union emerged as superpowers.

Decolonization accelerated after World War II, culminating in India’s independence in 1947 and a wave of African independence in the 1950s–60s. By the 1970s, most British colonies had become sovereign nations.

7. The Commonwealth and the Legacy of Empire

Though the formal empire dissolved, its legacy endures in the form of the Commonwealth of Nations—a voluntary association of 56 member states, most of which were former British colonies.

7.1 The Commonwealth Today

The Commonwealth promotes cooperation in trade, education, and human rights. Countries like Canada, Australia, and India play leading roles, while the British monarch remains its symbolic head.

7.2 Economic and Political Legacies

The British Empire left behind a shared legal and administrative framework, including parliamentary democracy, the English language, and common law. However, it also left deep inequalities, racial hierarchies, and border disputes—such as those between India and Pakistan, or in the Middle East and Africa.

7.3 Cultural Influence

British cultural influence remains global: literature, sport, education, and media continue to reflect imperial ties. Cities like London, Toronto, and Singapore are vibrant hubs of former imperial networks, now reimagined through globalization.

8. Controversies and Reassessment

In recent years, the British Empire has become the subject of renewed debate. Statues have fallen, archives reexamined, and curricula rewritten. Scholars and activists question whether Britain has fully reckoned with its imperial past.

8.1 The Debate Over Empire’s “Benefits”

Some argue the empire brought infrastructure, education, and modern governance to its colonies. Others counter that these came at immense human and cultural cost—slavery, famine, dispossession, and systemic racism.

The truth lies in complexity: the empire was neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but a multifaceted historical phenomenon whose consequences are still unfolding.

8.2 Reparations and Historical Accountability

Movements calling for reparations—for slavery, colonial violence, and economic exploitation—are gaining traction. Institutions such as the Bank of England and British universities have acknowledged their ties to slavery, while debates continue over returning looted artifacts from museums.

9. The British Empire in Modern Perspective

Today, the British Empire is often viewed through the lens of global history rather than national pride. Its impact on trade, migration, and cultural exchange shaped the interconnected world we live in.

9.1 Migration and Multiculturalism

Post-war migration from the Caribbean, Africa, and South Asia transformed Britain itself into a multicultural society. The “Windrush Generation” brought new identities, cuisines, and music, redefining Britishness.

9.2 Language and Globalization

English, the imperial language, has become the world’s lingua franca—used in diplomacy, business, and the internet. This linguistic legacy, while born of empire, now unites diverse cultures worldwide.

9.3 Lessons for the Future

The British Empire’s story is a cautionary tale about power, greed, and cultural arrogance—but also about human resilience and adaptation. Its history reminds us that global dominance comes at moral cost, and that the true measure of a nation lies in how it faces its past.

Conclusion: Empire Remembered, Lessons Learned

The British Empire was a global phenomenon of immense complexity. It built railways, cities, and institutions—but also exploited people, resources, and cultures. It connected the world through trade and language—but fractured it through racial hierarchy and inequality.

Today, its legacy lives on in the institutions we use, the languages we speak, and the borders we inhabit. Whether viewed with nostalgia or regret, the empire’s history is inseparable from the story of the modern world.

Understanding the British Empire is not about glorifying the past, but about learning from it—so that power, in whatever form it takes, is wielded with responsibility, respect, and humility.

Disclaimer:

This article is intended for educational and informational purposes only. It does not glorify or justify colonialism or imperialism in any form. The goal is to provide a balanced historical overview of the British Empire and its colonies, highlighting both its achievements and injustices. Readers are encouraged to consult diverse scholarly sources for a deeper understanding of this complex subject.